When asked whether euthanasia was ever appropriate, one Tibetan teacher laughed gently and said, “You aren’t serious, are you? That would be killing.”

Another Tibetan teacher, when asked the same question, replied, “This is very tricky. Suppose you are sitting in your living room and you hear a screech of brakes. You go outside and you see that your dog has been hit by a car. His body is broken and he is obviously in great pain and is going to die. You go into your house, get a gun, and shoot him. What’s wrong with that? But if you hesitate for a moment and think about how you don’t want to take care of your injured pet, everything changes.”

The first precept in the Buddhist monastic and lay ordinations is not to take life. The commitment is specifically not to kill a human being, but the principle is usually applied to all sentient life. At the same time, the fundamental intention of Buddhism is to end suffering. If two highly regarded teachers can have different views on the question of euthanasia, what are you to do when faced with the decision to kill or not to kill?

A three-step practice from Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche provides a guide:

- See clearly

- Know what is

- Act without hesitation

See clearly

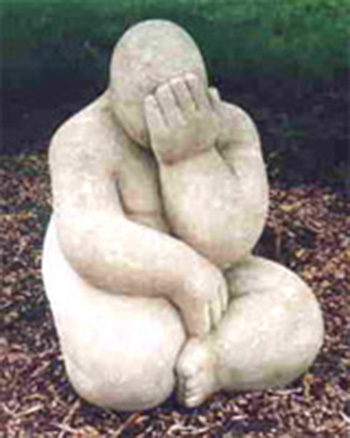

Cultivate a gesture with compassion. Because compassion puts you directly in touch with suffering, it penetrates the blinders of accepted values in a culture, a tradition, a nation, or a family. With the eyes of compassion, you cannot ignore the destructive effect suffering has on others.

Know what is

Eliminate the distortions caused by projections and conditioning. Open to the pain inherent in the situation whenever the question of killing arises. Open to all the complexities of the situation and know what is.

Act without hesitation

Rely on that knowing and act. Don’t let thinking confuse you. Serve what is true, not what is convenient. Act without hesitation and accept the results of your action.

Killing motivated by self-preservation, by trying to satisfy emotional needs, or by trying to be somebody is immoral. These motivations are based on a sense of being separate from what is. We perceive a threat to a boundary we have established and the most basic reaction to such a threat is to destroy its source. For example, you kill your injured dog because you feel threatened by the need to care for it.

Given the complexity of life in contemporary society, killing or involvement with killing is unavoidable. Biological, social, or political demands can conflict with the intention not to take life. We eat food and wear clothes produced by processes that involve someone taking the lives of animals. We kill insects and rodents to prevent them from invading our homes or spreading disease.

We kill in subtler ways as well. A harsh word may instantly kill years of trust. A derisive comment may kill inspiration in another person. We may kill a relationship by taking the other person for granted. Again, we do such things because we are reacting to some perceived threat.

Precepts are descriptions of how a person who is awake does behave. They help us to wake up to what is. They are not rigid rules. No rule can cover all possible circumstances.

Deep questions about values and ethics arise around the issues of abortion, life support, and elective suicide for those with debilitating and terminal illnesses. In these and other circumstances, call up compassion so that you see clearly, go empty in all the complexities so you know what is, and in that knowing act without hesitation.

Most people regard freedom as the ability to do whatever they want. In Buddhist practice, however, freedom means freedom from an agitated or clouded mind. As you cultivate this three-step practice, you discover a deeper freedom in your life: your every action becomes an expression of what you are — the union of compassion and emptiness.