Emotional Reactivity 2

Ken describes three levels of capacity. At the highest level, we can develop the capacity to experience emotions fully rather than expressing or repressing them. When that's not possible, practice taking and sending to generate a seed of virtue. When that isn't possible, avoid harming anyone and recognize you've got work to do. Ken also responds to student questions about fear of death, nightmares and being clear about why we practice.

Three levels of capacity

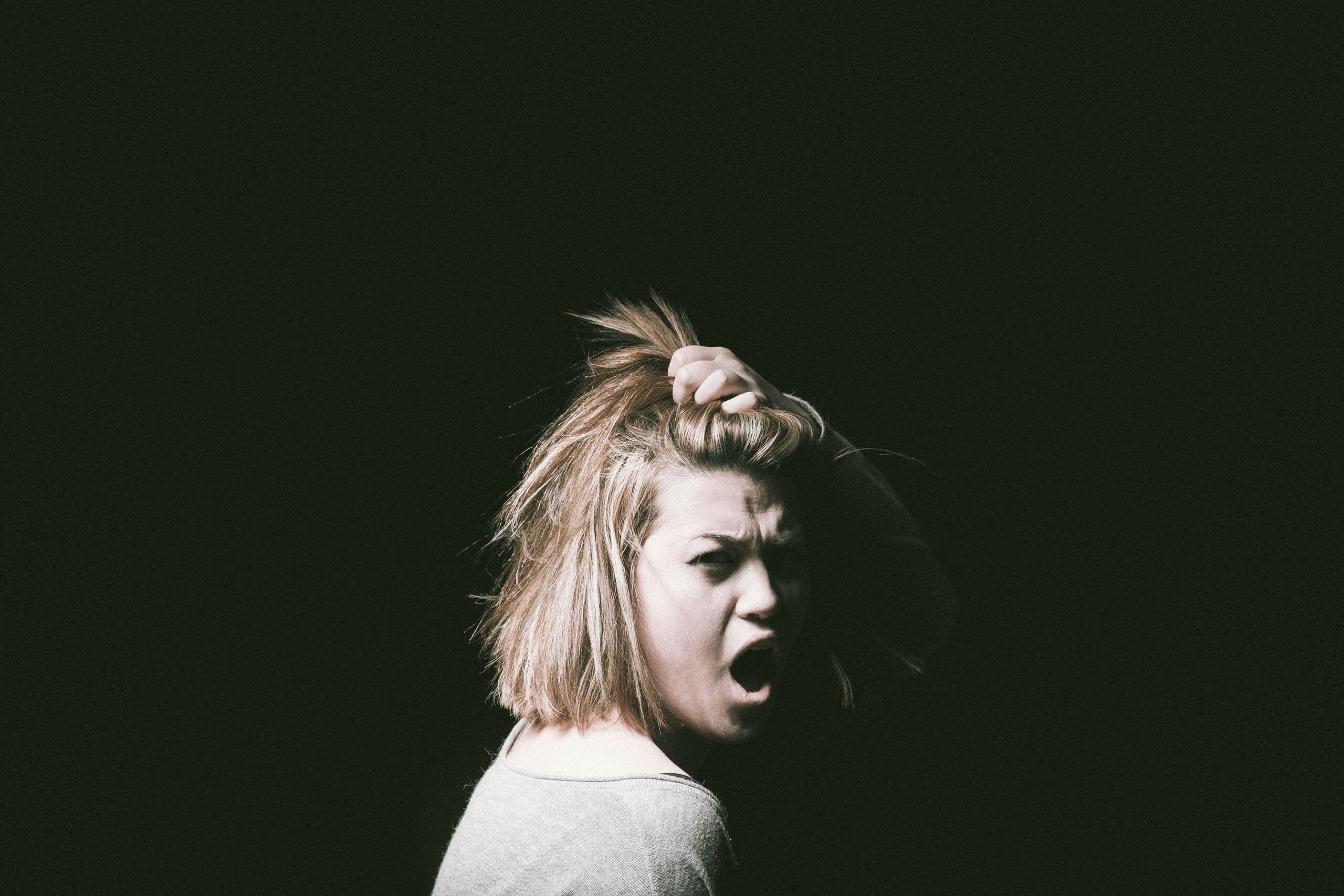

Student: Often, we find it more and more possible to figure out when we’re starting to feel an emotion to be able to recognize it. What’s frustrating sometimes is, great being able to recognize it, or, oh, I’m just about to get really angry.

Ken: Sorry. I didn’t hear the last part.

Student: It’s it’s really, it’s interesting through meditation. Like when we’re out in the world and we can realize, “Oh, I’m just about to become really angry,” and you want to work on that, but it’s impossible. What’s crazy is trying to, “Okay. I’m going to be real. I’m going to be really angry.” Like, you feel yourself starting to keyed up, you can recognize it. That’s something you’ve talked about, but there’s so many different levels of it. You think you’ve handled it and are able to relax yourself, but then all of a sudden it just comes back, this huge wave, and then, “Okay, I need to work on it.” So do you have a strategy for letting some of it go? How do you steam out? You know what I mean? So that it doesn’t keep catching you. Is that clear?

Ken: Yeah. Yeah. Well, first congratulations. Just from your description, your practice is quite effective. And you’re quite right, as we sit, we develop an ability to recognize what’s actually happening in us. And then we find it is usually a lot more powerful than we realized. It reminded me a bit of my old office partner. You know, I was at a celebration of his 70th birthday on Friday night, and he said, he’s changed a little bit, but he started off as a student of mine and we ended up doing a bunch of things together. Now this is one angry dude. He was the kind of guy that if you cut him off on a freeway, he would follow you home and punch you out.

He was a very successful businessman, but he was a really, really angry guy, extremely volatile, flying off the handle and firing people at the drop of a hat. Sound familiar? Okay. Just want to make sure we’re in the same ballpark. One day I needed to ask him a question. I came back to his office and he was sitting there like this, his feet up on his desk, his arms folded, and this look of severe impatience on his face. And I said, what’s the matter, Dave? He said, “It was a hell of a lot easier when I just got angry.” Because when we express the anger, we don’t feel it. Everybody else does.

When we suppress the anger, we don’t feel it. It goes into our body and causes illness, stress, what have you. What we’re learning through developing this capacity in attention is a way to experience what arises. So it doesn’t go out into the world and it doesn’t go into our body. We have spent much of our life not doing this. So it’s both a skill and a capacity, and it’s not something that you’re going to just turn on a switch and be able to do. It’s as you totally accurately observed and commented on. There are levels; there are degrees.

You know how family relationships are. They can be a bit intense. Many years ago, my older brother said something to me, and I got out of the room very quickly. I went and sat down for 45 minutes. Every cell of my body was inflamed with rage. I had developed the capacity to experience that, but it was pretty intense. It didn’t go to him and it didn’t go into my body. I experienced it. And that made a very big difference. There’ll be many, many things like that. So there’s both the skill—knowing how to do it—and the capacity, developing—you might say—the strength or the quality in attention that allows us to do that. And that’s what we do when we practice. We are actually developing both of those. But that is only half our practice.

The other half of our practice is what we do in our lives. And here again, you’re saying, “Okay, there it is,” and now you’re recognizing it. And you feel how deep and how powerful it is. In my own training, in Buddhism, we have three levels of morality, you might say, which correspond quite precisely to levels of capacity. We could start at either end, but I’m going to start at the higher end here. The first is, if we have the capacity, we just experience it. And that’s very interesting. In your case, anger, and there you are, and suddenly somebody says something and there’s this volcano going off inside you. Can you experience the volcano? Okay. If you can, great. You can continue with the conversation while you experience the volcano. It gets a little intense, but its doable. But that’s not always possible.

So the second level is, “Okay, I can’t just experience this.” So we do something with it. And in this, in the way that I was trained, what we do with it is we use that anger to generate a seed of virtue.

Student: Seed of virtue?

Ken: Yes. And this is a technique in Tibetan Buddhism known as mind training. And if you go up on my website, unfetteredmind.com, you’ll see a link to mind training, and there’s going to be more there than you want to know. But the technique comes down to something very simple. Whatever we’re experiencing that is unpleasant, we take the same unpleasantness from everybody in the world and we give to them whatever joy or happiness we’re capable of.

So there you are in anger. “Oh, I’m just about to punch this guy in the face. May all the anger of the world come into mine,” and you breathe in. And in that you’re generating a thought of compassion. You’re generating a thought of compassion by taking in the anger of the world, you are freeing the rest of the world from anger. You get it all [Laughs]. A little tough, but we tend to be extreme in the Mahayana.

So, “May all the anger in the world come into this anger of mine. May I experience it for everyone.” That’s an astonishing intention. And then as you breathe out, “May all the happiness and well-being that I enjoy in my life go to everyone, including this person that I’m a little annoyed with right now.”

And again, that’s an expression of compassion, or more accurately, that’s actually an expression of loving kindness. And so there it is. And again, that’s something you can train in meditation, but it changes things right in the moment, because when you take that anger in and you express that happiness and joy out, you change your relationship with your own anger. Do you follow? And that allows a bit more space so that it doesn’t just run. Okay?

The third level is when we can’t do that. In the third level, there are certain actions that we just won’t do: we won’t hit somebody, we won’t hurt somebody, we won’t speak maliciously to somebody. And our own commitment to those ethical guidelines inhibits the actual expression of the anger, so it doesn’t harm anybody else, and we get to work with it on our own. So you have those three things. One is, “Can we just experience it?” Great, then it’s just an experience. If it’s not possible, “Can I do something with it?” And what I offered you, there was a seed of compassion. Okay. If that can work, great. If not then, “Okay, I’m not going to hurt anybody, but I’ve got some work to do.” Does this help?

Student: That’s great. Thank you.

Ken: Okay.

Be clear about your intention

Michael: Michael from Seattle. I have a question that’s more personal about my practice currently. I’ve had sort of a bumpy year with a lot going on in my life and then some recent orthopedic challenges. And, what I found was I was very anxious for a while and it was very difficult for me even to sit down to practice. I had quite a bit of anxiety, so I shortened my sessions and made it through that. But most recently I’m sensing quite a bit of resistance in my practice. And I think what’s coming up for me is two things. One I’m feeling disillusioned, about where my life is, come to this point, but also some regret for past decisions. So I’m wondering if you could give me some guidance about how to make it through this particular phase of my practice?

Ken: And you think it’s going to change? Well, let’s entertain something for a moment. Suppose I could say something which got you through this particular phase of your practice, then what?

Michael: Well, if I had to guess I’d probably bump up against something similar in the future.

Ken: So what would be helpful to you?

Michael: Well after this morning’s sessions I think one thing that might be helpful is actually to refocus on my intention and why I’m doing this in the first place. And I think that that actually was an interesting question this morning.

Ken: I think it is important as you say, because there’s a tendency, when we engage in spiritual practice, to accept what other people have found as answers as if what they found will answer our own questions, whatever they may be. In the 11th century, there was a Tibetan individual by the name of Khyungpo Naljor who started off by becoming a Bön priest. Bon was the native religion in Tibet. And he became a very proficient lama, a highly respected Bon priest, but the teachings of Bon didn’t satisfy him. So he thought he should go to India. But his parents didn’t want him to go on a long, dangerous journey. So he found a dzogchen teacher and studied with him for a while. Didn’t work.

Then he found a mahamudra teacher. Studied with him. And after a few years, the mahamudra teacher said, “Well, you understand that everything that I know,” to which Khyungpo Naljor said to himself, “Well, then you understand nothing, ’cause I understand nothing.” So at the age of 57, which is like at the age of 77 in our culture, he set off for India. And studied with 150 teachers. He was pretty serious about this stuff. Eventually ran into Niguma and Sukhasiddhi, two women masters, where he found the teachings that answered his questions. He came back to Tibet and became very, very famous teacher, basically the founder of the Shangpa tradition.

But I like this story because it tells us that we have to find our own path and we have to be clear about our intention of what we’re looking for and not accept what somebody else has discovered. We can learn from it, try it out. Maybe it works, but in the end we have to discover it in our own experience. We have to make it our own. And that’s challenging. That’s why we have to be extremely clear about our intention because it’s only by being clear about our intention that we’ll have the strength and the determination that it takes to bring this kind of energy into the practice. Okay?

Michael: Okay. Thank you

Recurring nightmares

Announcer: This question is from Anna in the Netherlands: “For many years, I’ve been having very vivid nightmares in which I am being chased by scary men who wanted to kill me and do other terrible things to me as well, like rape and torture. The dreams are so realistic that I sometimes wake up literally feeling the physical consequences. These dreams are pretty traumatic, and my question is what can you advise me regarding how to deal with these recurring nightmares? I’ve read a lot about your approach with attention. And this sounds very appealing to me.”

Ken: They sound like quite unpleasant dreams or nightmares, as you say. I think it’s probably good to look at how you are preparing to go to sleep. Maybe before you go to sleep, spend a few minutes, anywhere from five to 15 minutes letting your mind and body grow calm. Meditation, of course, following the breath, or if that doesn’t work for you, then maybe just listening to some pleasant music so that when you go to sleep your body and mind are already relaxed. I think that will help you to sleep and I think it may have some benefits over the long term.

Next place to focus some attention possibly is when you wake up from these nightmares.

When you wake up, there are a couple of things you could do. One is, as soon as you become aware that you’re awake, open to the experience of breathing and feel how your body is. There probably will be some physical reactions to these dreams, and emotional, and you just let yourself experience that as you breathe. Not trying to intensify it, but not trying to make it go away either. And as you experience it, just remind yourself gently, this was a dream and this will help you to become less reactive to these experiences.

The second thing you can do is, as soon as you become aware that you’ve had one of these nightmares and you’ve woken up, is to do a practice we call taking and sending, which is to take in that kind of fear and terror and disturbance from all people, and give your own joy and happiness and well-being to them, imagining that all that terror comes into you like black smoke and all your joy and happiness goes out like white light. Doing this with each breath in and out. You do that for a few minutes. Now this may sound rather bizarre, but when you do this, you form a different relationship with your own experience and you’re generating a very positive attitude in your heart and that can also lead to change.

I think it would also be good to consider that, at some point in your life, you experienced something very frightening. And maybe during the day, sometimes just to recall the feelings of those nightmares and just spend a few minutes just resting in that experience, not trying to make it more intense, but just recalling it, so you actually accustom your body and mind to experiencing that knowing that it’s a dream. And I think this may also help to help you to form a different relationship with these experiences. So I think those are my main suggestions for you. I hope they help.

Fear of death

Elena: Hi, my name is Elena. I come from Florence, Italy. And this is my question. I have a strong fear of death among other fears, but that’s definitely the strongest one. And anytime I come to it in practice or in life, I tend to feel disoriented and I tend to freeze. I tend to, you know, I just want to stop because it’s just very painful and I don’t know exactly what kind of component or what kind of components are in that kind of fear, but my question is, could you tell me if there’s a way to approach it, in practice, or just one of the ways in which I could start you know, dealing with it basically?

Ken: Well, the first thing is that the fear of death is biologically conditioned into us. You have two cavemen walking along. They hear a growl. One of them says, “That’s curious,” and the other one says, “I’m outta here.” Whose genes get to survive? Not the one that’s curious. So over many thousands of years, we have very deeply conditioned for the body to react in certain ways when there’s any perceived threat. So you say that you fear death. Now, can you give me an example of a situation or an event in your life where this has come up in the way that you think is problematic for you?

Elena: It has nothing to do with a threat. It’s I think it’s a mental image somehow. It’s just the thought of not being here or not being also surrounded by people. It’s you know, it’s, it’s definitely a lot of things.

Ken: So when you think about dying, you think about not existing anymore.

Elena: Yes.

Ken: Then something in you freezes?

Elena: Absolutely.

Ken: Well, as the doctor said to the patient, when the patient said, “I always get a pain, when I do this.” The doctor said, “Well, don’t do that, then.”

Elena: It’s that simple?

Ken: But I suspect it’s not that simple. So this comes up unpredictably.

Elena: Let’s just say that it’s the deepest fear that I have. So if, I you know, if I find myself in my life where it’s very stressful condition, that’s probably the moment where I reach that state of mind. But it it also happens when I spend quite a long time by myself. So my, my brain tends to go around and, and tend to go there.

Ken: Well, from what you’re describing, I think the first step is to train your mind. Rather than meditating on death or anything like that, just to train your mind. So that when you’re under stress, when things are pressured and so forth, you develop the habit of focusing on your breath so you can calm things down inside, even if you can’t calm things down, outside. And that usually helps in stressful situations by itself. But as you develop this into something that you can do, even in stressful situations, then your mind just won’t go to those negative places.

Elena: It’s true. Although that particular thing is present. I mean, it’s pretty much always present.

Ken: The fear of death?

Elena: It’s always right there. I don’t look at it, but I know it’s right there. So sometimes I sort of, I open a little door and it helps.

Ken: What happens if you have tea with it?

Elena: If I have tea with it? [Laughs]

Ken: You know, you invite, is it death or the fear of death?

Elena: No, I’m sure it’s fear.

Ken: Okay. So you invite the fear of death and you have a cup of tea. What would that be like?

Elena: I don’t know.

Ken: Just imagine. “Well, fear, I don’t like you being here, but I’ve been trained to have good manners. I’m going to serve you a cup of tea anyway.” What would that be like?

Elena: Well, you know, I’m gonna try to plan a tea session every day. [Laughs]

Ken: A lot of the times we have these fears and we fear what we don’t know. So if you have tea with it, you get to know it. So you practice meditation every day?

Elena: Well, every day is a strong concept. But I try to.

Ken: Okay. Sometimes when you meditate, just invite fear of death to meditate with you.

Elena: Okay.

Ken: Now, you don’t have to have him or her sit right beside you because that may be a little too strong. You say, “Can you sit over there at the other side of the room?” But the fear of death is in the room. Now you meditate, and the fear of death is in the room, and you’re going to feel the physical reactions to that and the emotional, but because he’s on the other side of the room, it’s not going to be really strong, you follow? You can put him further away. You can put him on the other side of the city if you want, just as long as he is in your awareness. And then you just meditate, but you’re feeling some of the reactions and you realize, “Oh, I can feel these reactions and the world doesn’t come to an end.” And little by little, you can move death, the fear of death closer and closer until you can meditate with the fear of death right beside you. Now, what you’re learning here is not to ignore or block the fear, but how to be present in the fear and not be overtaken by it or overwhelmed. This make sense to you?

Elena: Yeah. Okay.

Ken: You can try that.

Elena: Thank you.

Ken: You’re welcome.