Body Sensations and Other Questions

Ken explores how to work with physical challenges in meditation, such as injuries, illness, and discomfort. Responding to practice questions from students, he emphasizes listening to the body and adapting postures to meet individual needs. As Ken says, “The stability of attention that develops by being in your body experience allows you to feel those old associations and experience them, and not to be carried away by them.

When sitting in meditation is impossible

Carol: When I first started sitting tonight, I was feeling quite okay, quite settled, kind of present, feeling sort of like a mountain for a moment. And I have had a very bad injury to my tailbone and sitting for the last few years has just been nearly impossible. So, I don’t sit. I mean, I kind of lounge a lot [laughs]. And so sitting here tonight, this is not a pain that I should be having. I can feel that it’s probably a destructive pain rather than a pain I should be with. And it’s extremely distracting and disruptive and agitating because I feel like I shouldn’t be sitting. I finally just put this pillow back here, which helped. But it’s really different from a pain that I’m willing to allow to work through or just to be with. And I don’t really know what to do about that.

Ken: [Sighs] That’s difficult.

Carol: It’s very present right now.

Ken: Now, is it present only when you’re sitting on a chair like this?

Carol: Yes, well that’s why I don’t sit on a cushion.

Ken: Yeah, because that just exacerbates it even worse. Right?

Carol: And I’ve been to ten-day retreats where I laid down a lot of the time. But then I just feel so awkward and embarrassed. What am I doing here lying down, you know?

Ken: Yeah. [Sighs]. We’re animals. We live, we have a body. We are our body. That’s unavoidable. And if sitting is pressing on a bone injury, then it is probably not a good thing. So please don’t feel that you have to, and you can lie down or whatever is better. You don’t have to sit in a chair. It’s very difficult to accept the limitations of our body, particularly when we’re engaged in a practice which incites all our idealism, isn’t it? We just want to do it this way.

Carol: Well, it distracts me to the point that I’m so agitated that all mindfulness really goes.

Ken: Exactly. And that’s not helpful. So you learn to meditate in a different position. That’s all there is to it.

Carol: It’s very hard for me to accept this.

Ken: I understand.

Carol: I like this figure up here. This feels very good to me.

Ken: Which one is that?

Carol: The one lying down. The resting Buddha.

Ken: Well, yes. And that’s our idealism coming up. But as I said before we started meditating, the body needs to be able to rest. And when you see people in these very, very straight postures, they’re resting in those postures. They’re not rigidly held there. And if it’s impossible for your body to rest sitting on a chair or on a cushion, because it is pushing a place in the body where there’s an injury and there’s pain, then that’s not the way to meditate. I’m sorry. That’s just how it is. And yeah, that may be very difficult to accept. I can really relate to that. But what’s important here is how much you want to do this, how important it is for you, or it is to you. That’s what’s important. This is something that is of vital importance to you, that you’re willing to endure pain in your body. Okay. So there’s no question about motivation here, right?

Carol: Well, this has actually made me sort of not feel very motivated.

Ken: Well, of course, because it’s painful. But you came here, you asked about this, so obviously it’s very important to you. Okay. So accept that it’s very important to you. That’s one part of the acceptance, and the other part of the acceptance is, “Okay, I’m not going to be able to do this the way everybody else does, but I’ll find a way.” But both things need to be accepted. Suzuki Roshi says in Zen Mind Beginners Mind, “Those who have a great deal of difficulty in sitting generally practice better, because it is through their imperfections that they discover their firm, way-seeking mind.” That makes sense to you?

Carol: Yes.

Ken: Okay.

Relate to illness as an experience

Announcer: This was submitted by Valerie in Washington, “How do I practice when ill? How do I work with the decreased energy?”

Ken: There are many practices one can do when one is ill, but for me the simplest—and again, for me, the most effective—has always been taking and sending. I find it very, very helpful. And it’s something you can practice when you have virtually no energy at all. If one is seriously ill, one is usually in a great deal of pain and discomfort, and if not actual pain, then certainly a lot of anxiety. And so you take in the suffering of illness from all beings and you give whatever happiness, joy, wealth, support, or care you’re receiving. And you give that away to all sentient beings.

And imagine taking in the suffering in the form of black smoke and giving away a form of white moonlight, just synchronizing that with the breath coming and going through your nostrils. It may sound like a strange practice to do, but it has the effect of encouraging you to relate to your illness as an experience. It is just something that one is experiencing. And as you rest in the experience, or as you use taking and sending to rest in the experience of being ill, then many of the emotional reactions to being ill dissolve. And so you find yourself fighting the experience of illness less, which takes a huge burden off the body and mind.

And you’re really working with the essence of Buddhism, that, “This is an experience; can I experience this completely?” This I find works even with decreased energy. Because when I’m ill, yes, you usually say the energy is low. And you start doing taking and sending, you may fall asleep, and now you’re resting and giving your body the opportunity it needs to heal itself. And you wake up and you continue with the practice, and you may go in and out of this, but now, as I said a few moments ago, you’re not fighting your experience. I think it’s important to remember that in Buddhism, it’s not about becoming Superman or Superwoman. It’s about being able to experience what happens to be arising. So if we’re ill, that’s what’s arising. That’s what we experience.

Listen to and ground your experience in the body

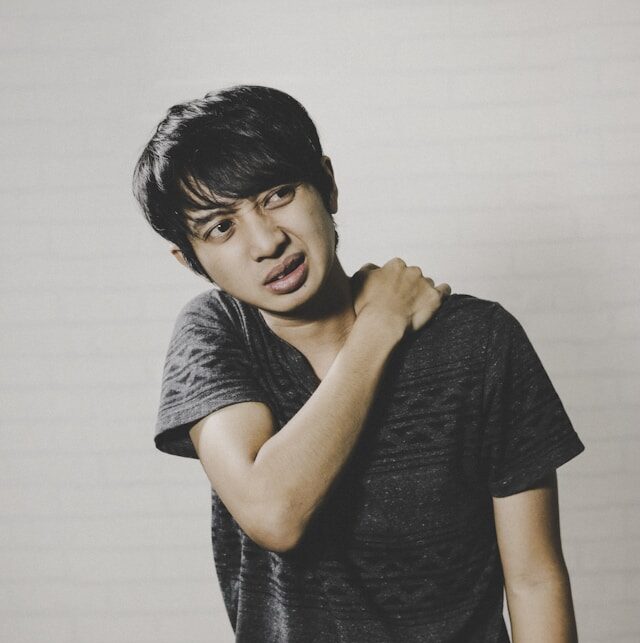

Mike: My name is Mike from Hollywood Hills in California. My question is how do you understand what your body, your physical being, is saying to you?

Ken: [Pause] You listen to it. Now, when I say, “listen to it”, it’s not going to speak in words. And if you think it’s speaking in words, then you’re just engaging in a certain kind of thinking, not helpful. Usually we’re going to do this when we’re dealing with something that’s bothering us in some way or another. And what I suggest to people is that you sit and just feel what’s happening in the body. Now, do you have something which is bothering you or something you’d like to use to explore this right now?

Mike: Sure. In my body recently I became aware that my blood pressure was fluctuating rather wildly. By accident, I went to a drug store and just took my blood pressure, and then I kept monitoring it, and it would go from like 130 to 170 in the doctor’s office within a minute. And I said, “What is my body saying? What is this about?” This surprised the doctors. And then my pulse, which has been true all of my life, I have a skipped heartbeat, every fourth beat. And I would go like, “This has come and gone from me.” But I’ve done enough practice to know this is talking to me on a very complex, deep level. And I started thinking and feeling, what did this mean for me? And was it natural or was it a reaction to the death of the ego, for example, the struggle between freedom and past behaviors? Was it anxiety? This is what I was coming to, but I wasn’t really sure. And how a teacher or someone, as you have said in your book, was necessary to see, what really was this? Because my inner self of my body has such a complex universe with such inner intelligence, that it is capable of saying things that my mind really can’t comprehend.

Ken: When we talk about listening to the body, we’re not really talking about physically measurable things like blood pressure and heartbeat or skipped heartbeats. That would just take us into a realm of speculation and we’d wind up in a big mess of stories. To understand the significance of those, then you’re much better off interacting with your doctor and saying, “What pathologies, if there are actually pathologies or abnormalities, are those indicative of?” And then you get appropriate treatment, whatever form that may take. It’s relatively unlikely that any of those things are going to reflect what you’re calling “the death of ego” or something like that. But when I say, “Listen to your body”, has anything upset you in your life in the last week or so?

Mike: [Sigh] I …

Ken: This isn’t tied to what symptoms you may be experiencing. I’m just interested in using this as an example. For instance, you related to me how when you were describing a certain painting, you had some very deep feelings. Okay? So recall that incident, and as you recall it, certain physical memories are likely to come to you. Okay? Now simply breathe and experience those physical memories, not the emotions just yet, and not the stories associated with them, just the physical sensations. Okay? Now, when you can rest in the experience of those physical sensations, then you develop a certain stability of attention in the body. It’s more solid because you’re connected with the body. Are you with me?

Mike: Yes.

Ken: Okay. Now, on the basis of those physical sensations, you can include the emotional sensations. When you open to the physical and emotional sensations, what do you experience?

Mike: A sense of solidity actually. It’s that the two things are coming and becoming like a solid object, like a solid experience about it. But it’s not a particularly emotional experience recalling them. It’s as if I feel sort of like the physical sensations are calming the emotional current of what I was feeling at the time. So the emotional current doesn’t seem as overwhelming as it did actually in the real experience.

Ken: So by listening to your body, you ground your experience in the body. That allows a higher level of attention to develop. In that higher level of attention, you’re not swept off your feet or carried away by the emotions that are arising. And thus you are more present in the experience. So this is what is meant by understanding your body. It’s not all that medical stuff. It’s very immediate, very experiential. It’s not conceptual at all.

Mike: Thanks. It’s interesting to me because I was in a session with a Buddhist psychotherapist, and I really have felt there have been massive changes going on in me and with my body and in my centeredness. But at the same time there’s been what feels like an anxiety or fear in my body, sort of a corresponding thing. And when I was reading your book, it did seem like when I was reading about the death of the ego and the life and death struggle between old ingrained patterns and fears of mine, like, “Oh my God, my father is going to kill me,” which was also involved in that painting experience. Or if I make myself feel really sexual or out in the world, physically, I’m literally going to be killed the way I was in childhood. And that vibration in the body seems to fight the outer calmness that’s going on with me at the same time.

Ken: The stability of attention that develops by being in your body experience allows you to feel those old associations and experience them, and not to be carried away by them. And when that happens, the subjective experience is that they often feel more intense. They aren’t actually more intense. You’re just experiencing them in attention, maybe for the first time. And when you experience them in attention, that is, you experience them and stay present in your body or in the room or whatever, in now. That’s what leads to the change of relationship with what you’ve been describing. And the consequence of that, when you do this enough times, is that you become less reactive, because now these move from things that you just couldn’t experience before to, “Oh, this is just an experience.” Okay?

Mike: Yeah. Thank you.

Ken: You’re welcome.

Vivid physical sensations

Announcer: Here’s a question from Pat in northern California, “I’ve been practicing shikantaza meditation under the guidance of a Buddhist priest for 24 years. My teacher died a year and a half ago, and there’s no one to answer this question. Following the directions in your online mahamudra lectures, I experienced three distinct shifts with a rest after each. After the third rest. I’m unaware of anything until I experience one or two slightly painful, distinct heartbeats. These feel like my heart is restarting. I’m not aware of it stopping, only starting again, and only in reflection does it seem it has stopped, and also that some period of time has gone by. This kind of meditation seems to produce a sense of refreshment, like an afterglow. So does the heart stop? Have I perhaps misinterpreted the instruction to rest?”

Ken: I think when you describe the three distinct shifts, this probably refers to the lecture in which I gave the pointing out instructions where you’re looking at things from a different point of view and resting in the looking in each case. From what you describe here, it seems you’re experiencing a quality of resting, and it sounds like resting relatively free of thought, at least for a few moments. So when you say are unaware of anything, that’s something I would ask you to look at. Is it a blank state or is there some kind of knowing present? Often when we are resting, and resting deeply, when we start to move out of that, then physical sensations will be unusually vivid or a little more vivid than they are ordinarily. And I think that’s what you’re describing when you say, “One or two slightly painful, distinct heartbeats.”

I very much doubt that your heart is actually stopping. It doesn’t sound like that from the rest of your description here, because you said also that you feel refreshed and like there’s some kind of afterglow. This to me indicates that there’s some kind of resting there, and that your body is very peaceful, your mind is very quiet, and you may not be used to that. I don’t know. But when you’re coming out of it, then everything takes on some kind of heightened awareness or vividness for a few moments. I think that’s what you’re experiencing there. So the fact that you feel refreshed and have a sense of awareness, as I’m interpreting this, to me doesn’t indicate a problem, but I can’t tell of course.

Generally, there can be all kinds of things that happen in meditation. My teacher used to say that meditation experiences are like the flowers in spring in the mountains, all kinds. But they come and they go. If this kind of thing persists over a period of time or seems to intensify, then I would recommend the usual precautions. Just have your heart checked out by your doctor. But my own sense is that there probably isn’t a problem with your heart. You’re experiencing resting and then coming out of that resting. I would ask you, when you say, “I’m unaware of anything,” if it is really just a blank state, or if there’s some kind of knowing. If it’s a blank state, then you’re in a dull state, and this isn’t particularly helpful for meditation. If there is some kind of knowing, then you want to rest in the knowing.